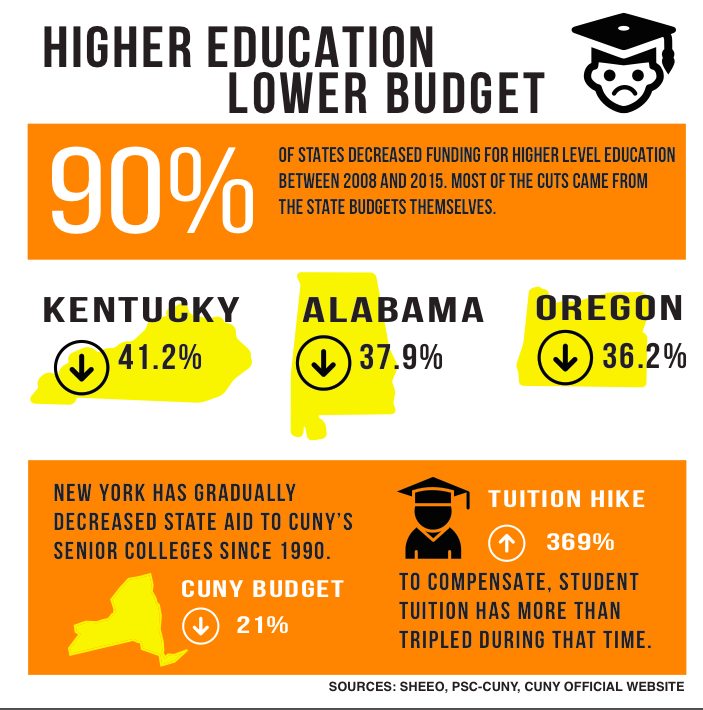

A front-page New York Times article discussed CCNY's financial problems -- and the lack of assistance for CUNY from the state. Here's our take: As financing for college plummets and tuition soars, students and faculty wonder who will stand up for the future of public education by Saif ChoudhuryAs a young boy playing computer games in his local library in Queens, Tarif Anzum never thought he’d be a physician. But that’s where he’s headed – he hopes. The son of a cab driver, Anzum worries constantly about money. As a fourth-year Sophie Davis student at City College, most of his medical training remains ahead of him and he often wonders how he will continue paying for it – and cope with his future debt.“I am well aware of how my friends in private schools end up paying close to half a million dollars in the long run to become doctors,” says Anzum, whose family immigrated from Bangladesh when he was four years old. “CCNY is much more affordable, and I know that if I had gone to any of those private colleges, I would be in so much more debt than I am in now. [Still], money is becoming more and more of a problem than it should be for public education.”Anzum offers a stark example of the ways growing numbers of us, especially first-gen college students, rely on the public system in an age of skyrocketing higher education costs. While the media often focuses on the struggles of students at elite universities – where tuition often totals over $50,000 a year -- for the past few decades, the price tag of public colleges has also gone up. At the same time, the public investment in colleges like ours has spiraled downward.According to the American Council on Education (ACE), state fiscal investment in higher education has been in retreat since about 1980, despite a growing demand for higher learning. In fact, if current trends stay the same, the average state fiscal support for college education will reach zero by 2059 – although it could happen much sooner in some states. The State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO) reports that as the cost of education per student has gone up in the past 25 years, the average amount states spent per student went from $8,688 in 1990 to $6,966 in 2015.

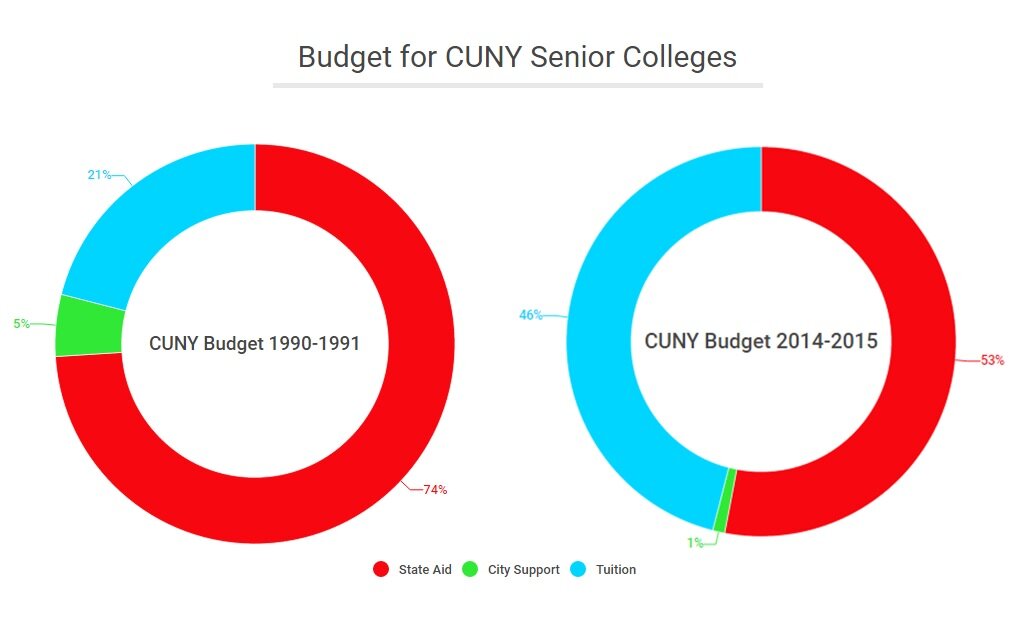

A front-page New York Times article discussed CCNY's financial problems -- and the lack of assistance for CUNY from the state. Here's our take: As financing for college plummets and tuition soars, students and faculty wonder who will stand up for the future of public education by Saif ChoudhuryAs a young boy playing computer games in his local library in Queens, Tarif Anzum never thought he’d be a physician. But that’s where he’s headed – he hopes. The son of a cab driver, Anzum worries constantly about money. As a fourth-year Sophie Davis student at City College, most of his medical training remains ahead of him and he often wonders how he will continue paying for it – and cope with his future debt.“I am well aware of how my friends in private schools end up paying close to half a million dollars in the long run to become doctors,” says Anzum, whose family immigrated from Bangladesh when he was four years old. “CCNY is much more affordable, and I know that if I had gone to any of those private colleges, I would be in so much more debt than I am in now. [Still], money is becoming more and more of a problem than it should be for public education.”Anzum offers a stark example of the ways growing numbers of us, especially first-gen college students, rely on the public system in an age of skyrocketing higher education costs. While the media often focuses on the struggles of students at elite universities – where tuition often totals over $50,000 a year -- for the past few decades, the price tag of public colleges has also gone up. At the same time, the public investment in colleges like ours has spiraled downward.According to the American Council on Education (ACE), state fiscal investment in higher education has been in retreat since about 1980, despite a growing demand for higher learning. In fact, if current trends stay the same, the average state fiscal support for college education will reach zero by 2059 – although it could happen much sooner in some states. The State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO) reports that as the cost of education per student has gone up in the past 25 years, the average amount states spent per student went from $8,688 in 1990 to $6,966 in 2015. Where does the rest of the money come from? Almost all of the nearly $10,000 a year tuition that the average U.S. student pays comes straight from our pockets. The drop in state funding for public education has become a hot button issue. Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton has weighed in, and Bernie Sanders believes that tuition should be free. President Obama, who has made college affordability a key issue, said: “Higher education should not be a luxury. It is a necessity, an economic imperative that every family in America should be able to afford.”Yet this ‘necessity’ is becoming harder and harder to attain.CCNY Feels the PinchAt City College, widely considered an educational bargain at about $6,000 a year, tuition has climbed $300 a year for the past five years as Albany has turned its back on the CUNY system. Governor Andrew Cuomo's budget won't help matters -- though he backed off from a proposed cut.This hurts students like graduating senior Stephanie Saintilien of Queens. After transferring here from Marymount Manhattan early in her college career, she pursued everything from film analysis to pre-med but settled on English. As stressful as her studies have been, financial concerns have always posed issues. “I grew up in a two-bedroom apartment with five other siblings and a cat,” says Saintilien, who like just about every other CCNY student works to help pay for college. “But even though we were far from being financially wealthy, according to the government my father still earned too much for a living when he was working. So dealing with the headache of dealing with financial aid was very disheartening and frustrating.”It didn’t have to be this way. Since the 2008 recession, state funding for CUNY’s senior colleges has decreased by a full 17%, when totals are adjusted for inflation. The state’s economy and budget have rebounded since then, but CUNY has been largely ignored. In fact, an analysis by New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer revealed that if state contributions to CUNY had grown at the same rate as the state’s operating budget over the last seven years, the system would have received an additional $637 million – decreasing the pressure on students’ wallets. Given money issues, it takes the average student eight years to graduate from CCNY, and only 42% of enrolled students actually make it to graduation.

Where does the rest of the money come from? Almost all of the nearly $10,000 a year tuition that the average U.S. student pays comes straight from our pockets. The drop in state funding for public education has become a hot button issue. Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton has weighed in, and Bernie Sanders believes that tuition should be free. President Obama, who has made college affordability a key issue, said: “Higher education should not be a luxury. It is a necessity, an economic imperative that every family in America should be able to afford.”Yet this ‘necessity’ is becoming harder and harder to attain.CCNY Feels the PinchAt City College, widely considered an educational bargain at about $6,000 a year, tuition has climbed $300 a year for the past five years as Albany has turned its back on the CUNY system. Governor Andrew Cuomo's budget won't help matters -- though he backed off from a proposed cut.This hurts students like graduating senior Stephanie Saintilien of Queens. After transferring here from Marymount Manhattan early in her college career, she pursued everything from film analysis to pre-med but settled on English. As stressful as her studies have been, financial concerns have always posed issues. “I grew up in a two-bedroom apartment with five other siblings and a cat,” says Saintilien, who like just about every other CCNY student works to help pay for college. “But even though we were far from being financially wealthy, according to the government my father still earned too much for a living when he was working. So dealing with the headache of dealing with financial aid was very disheartening and frustrating.”It didn’t have to be this way. Since the 2008 recession, state funding for CUNY’s senior colleges has decreased by a full 17%, when totals are adjusted for inflation. The state’s economy and budget have rebounded since then, but CUNY has been largely ignored. In fact, an analysis by New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer revealed that if state contributions to CUNY had grown at the same rate as the state’s operating budget over the last seven years, the system would have received an additional $637 million – decreasing the pressure on students’ wallets. Given money issues, it takes the average student eight years to graduate from CCNY, and only 42% of enrolled students actually make it to graduation. From the top down, everybody is feeling the pressure. “As state funding decreases, financial issues are one of the most pressing challenges facing public higher education institutions across the country, including City College,” says Lisa Staiano Coico, president of City College. “It is in our best interest to be proactive in protecting the financial health of City College.”How? In the face of a $14 million budget crisis, CCNY has responded by freezing hiring, bringing in consultants and financial managers to examine the school’s bottom line and cutting courses, which makes class size larger. “Not being able to afford as many professors or have them teach several classes increases each class size by a sizeable amount,” says psychology professor Bill Crain who has been teaching for nearly 50 years. “That alone has such a debilitating impact on a student’s education. They have to write less because there aren’t enough resources to grade essays and papers – where a student really grows in their learning. The students also don’t get to know their professors, who will probably give them the connections and resources they need to succeed. On top of all of that, there isn’t enough money to fund projects, scholarships, and tutoring to facilitate academic growth. With more funding, the students would have been in such a better place.”Jose Cardoso, a junior at CCNY, speaks for many when he states that his educational experience has suffered due to a lack of funding to the CUNY colleges. “There are so many problems with the facilities at the college,” says Cardoso, who is the first of his immigrant Mexican family to pursue a bachelor’s degree. “Either the escalators aren’t working, or there are leaks in the libraries, or some rooms aren’t cleaned from the very start of the semester until the very end,” he observes. “Having these bad conditions doesn’t make me feel like it’s worth working so many hours at CVS to put me through this college.”Like other public colleges across the country, City is looking to recruit non-resident and international students who pay higher tuition rates. That adds up to a shrinking share of local students from lower-income families, who almost always require – and receive -- financial aid. Also, City College and other schools will have no choice but to follow the money. “CCNY will continue to build programs that attract more funding and will decrease support of programs that fail to do so,” says Professor Gordon Thompson who teaches Black Studies. “In short, CCNY will become increasingly a STEM oriented campus to the detriment of the humanities, arts, and social sciences.”Specific ethnic groups can suffer as well. Though located in Harlem, the de facto capital of black America, CCNY has seen a drop in enrollment in African-American students. In 1990, black students made up 40 percent of City’s student body, a number that has dropped by half 25 years later. “Since Hispanics are considered a minority, the College will have little incentive to pay attention to other minority groups such as black Americans,” says Thompson, who also heads the RAP-SI initiative, which focuses on black male success.“I expect to see a continuing decrease in the number of black Americans students at CCNY.”Are We Worth It? Yes!At the end of the day, there is only one way that the United States can reverse the trend of declining support for public education – by investing in our future. Outgoing student government president Kenny Soto summed it up simply: “The budget cuts are happening because people find that public education isn’t worth all the other factors in our state budget. [But], in fact, part of the pillar of a good capitalistic society is making sure that everyone has a good education – especially if that means that we are getting that education publicly as opposed to privately.”

From the top down, everybody is feeling the pressure. “As state funding decreases, financial issues are one of the most pressing challenges facing public higher education institutions across the country, including City College,” says Lisa Staiano Coico, president of City College. “It is in our best interest to be proactive in protecting the financial health of City College.”How? In the face of a $14 million budget crisis, CCNY has responded by freezing hiring, bringing in consultants and financial managers to examine the school’s bottom line and cutting courses, which makes class size larger. “Not being able to afford as many professors or have them teach several classes increases each class size by a sizeable amount,” says psychology professor Bill Crain who has been teaching for nearly 50 years. “That alone has such a debilitating impact on a student’s education. They have to write less because there aren’t enough resources to grade essays and papers – where a student really grows in their learning. The students also don’t get to know their professors, who will probably give them the connections and resources they need to succeed. On top of all of that, there isn’t enough money to fund projects, scholarships, and tutoring to facilitate academic growth. With more funding, the students would have been in such a better place.”Jose Cardoso, a junior at CCNY, speaks for many when he states that his educational experience has suffered due to a lack of funding to the CUNY colleges. “There are so many problems with the facilities at the college,” says Cardoso, who is the first of his immigrant Mexican family to pursue a bachelor’s degree. “Either the escalators aren’t working, or there are leaks in the libraries, or some rooms aren’t cleaned from the very start of the semester until the very end,” he observes. “Having these bad conditions doesn’t make me feel like it’s worth working so many hours at CVS to put me through this college.”Like other public colleges across the country, City is looking to recruit non-resident and international students who pay higher tuition rates. That adds up to a shrinking share of local students from lower-income families, who almost always require – and receive -- financial aid. Also, City College and other schools will have no choice but to follow the money. “CCNY will continue to build programs that attract more funding and will decrease support of programs that fail to do so,” says Professor Gordon Thompson who teaches Black Studies. “In short, CCNY will become increasingly a STEM oriented campus to the detriment of the humanities, arts, and social sciences.”Specific ethnic groups can suffer as well. Though located in Harlem, the de facto capital of black America, CCNY has seen a drop in enrollment in African-American students. In 1990, black students made up 40 percent of City’s student body, a number that has dropped by half 25 years later. “Since Hispanics are considered a minority, the College will have little incentive to pay attention to other minority groups such as black Americans,” says Thompson, who also heads the RAP-SI initiative, which focuses on black male success.“I expect to see a continuing decrease in the number of black Americans students at CCNY.”Are We Worth It? Yes!At the end of the day, there is only one way that the United States can reverse the trend of declining support for public education – by investing in our future. Outgoing student government president Kenny Soto summed it up simply: “The budget cuts are happening because people find that public education isn’t worth all the other factors in our state budget. [But], in fact, part of the pillar of a good capitalistic society is making sure that everyone has a good education – especially if that means that we are getting that education publicly as opposed to privately.” President Coico stresses that CCNY is worth every penny of investment. “We are a nationally ranked institution that secures more than $60 million in research grants,” she says. “Our students consistently win national and international awards; our faculty includes internationally renowned scientists, artists and scholars; and we are home to Nobel Prize Laureates and Oscar winners. As we launch our new strategic plan that addresses financial growth of the college, our goal is to reach new heights of distinction while staying true to the mission of access to excellence.”Professor Crain agrees that CCNY should stay true to its history and mission. “Since its opening in 1847, CCNY has represented a chance for the disenfranchised to make something of their lives,” says Crain. “But while funding for students has gone down, funding for state prisons has gone up. What does that say about the opportunities given by the current power structure?”

President Coico stresses that CCNY is worth every penny of investment. “We are a nationally ranked institution that secures more than $60 million in research grants,” she says. “Our students consistently win national and international awards; our faculty includes internationally renowned scientists, artists and scholars; and we are home to Nobel Prize Laureates and Oscar winners. As we launch our new strategic plan that addresses financial growth of the college, our goal is to reach new heights of distinction while staying true to the mission of access to excellence.”Professor Crain agrees that CCNY should stay true to its history and mission. “Since its opening in 1847, CCNY has represented a chance for the disenfranchised to make something of their lives,” says Crain. “But while funding for students has gone down, funding for state prisons has gone up. What does that say about the opportunities given by the current power structure?” He adds that our future depends on political will. “What most politicians and state governments don’t realize is that people are actually willing to pay taxes to fund things that they care about, like public education,” he says. “These leaders need to see that not funding opportunities for students only lowers their chance at a good education experience – an experience that all students deserve.”

He adds that our future depends on political will. “What most politicians and state governments don’t realize is that people are actually willing to pay taxes to fund things that they care about, like public education,” he says. “These leaders need to see that not funding opportunities for students only lowers their chance at a good education experience – an experience that all students deserve.”

Welcome to The Campus!

We’re glad you’re here. Look through our articles to find something that interests you. If you’re interested in writing, editing, photographing, drawing, designing, or social media managing for us, contact us at thecampus@gtest.ccny.cuny.edu or come to a meeting in NAC 1/119 during club hours.