Women Who Changed CCNY – and the World

Words by Michael Alles

Photographs courtesy of The City College of New York Archives

CCNY first openedits doors in 1847, for men only. The School of Business was founded in 1920 andallowed women to enroll, but mostly for courses in accounting, stenography, andother business office skills. The number of women eligible to register waslimited, and CCNY forced them to comply with difficult schedules that favoredthe men on campus. Women rarely, if ever, appeared in yearbooks, and if theydid it was usually department secretaries and administrative clerics. It tooknearly a century for the men controlling the campus to integrate women into thefaculty and student body.

The School of Technology first admitted women in 1938. Gladys Lovinger entered the school in September of 1938 after financial consideration prevented her from studying at MIT. Unfortunately, at CCNY, the patriarchy had other plans for her. Her misogynistic physics professor intentionally lowered her grades to prevent her from qualifying for civil engineering courses. Lovinger later left the college without a degree.

In September of 1943, Francine Danish Altman became the first woman to obtain a degree from the School of Technology, receiving a bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering.

Prof. Cecile Froehlich joined the City College School of Technology faculty in 1945. Born in Cologne, Germany, she had a long journey before coming to CCNY. She attended the University of Bonn, studying mathematics, physics, and philosophy. She received her Doctor of Philosophy Degree and moved on to work with the German General Electric Company as a scientific assistant to the Vice President. When Hitler came to power, her time at the company ceased, and she fled to Belgium. She found work for a large manufacturing company as a consultant mathematician, but just as she was getting settled, Hitler again forced her to flee. She escaped to France, and then to America.

Finding work in theengineering and industrial field in the United States was much more difficultfor Froehlich than in Europe. Being a woman and an immigrant subjected her toemployment discrimination in all fields of work, which was not uncommon in1940’s America. Eventually she secured a position with CCNY’s School ofTechnology, changing the school forever.

At the time of herretirement in 1966, she was the first woman appointed to the faculty of theSchool of Engineering and Architecture, the first woman at City College toobtain the rank of full professor, the first woman to be elected Chair of anydepartment, and the first woman to head any engineering department anywhere inthe United States.

In her 21 years atthe college, she largely increased the number of women admitted to the Schoolof Technology. She helped establish the City College chapter of the AmericanAssociation of University Women, and the City College chapter of the Society ofWomen Engineers. She also established a program to recruit women of color intothe sciences, engineering and mathematics.

Around the same time, in 1944, Margaret E. Condon came to City College to get a year of practical experience in the Veterans Rehabilitation Program. Born in 1904 to Irish immigrants in Bridgeport, CT, she moved to New York in 1930 to teach at P.S. 72 in the Bronx during the Great Depression. Her memoir - available in the CCNY Archives – details her experiences during the Depression and WWII. In an excerpt from her memoir she writes about her time at the 1936 Olympics:

“At the Olympics, Hitler was in the box nextto me. It was difficult for me to understand how people could give suchadoration to a man. When I mentioned it I was told by the German next to methat Hitler was their guide. Strange that the leaders in the world could notsee where Germany was headed.”

In 1948, four yearsafter coming to CCNY, she was appointed to a permanent position at the college,to direct a program for physically disabled college students. This program wasthe first of its kind in the United States and grew rapidly within its earlyyears. Condon also established a reading room for blind students, attractingstudents from all five boroughs because other colleges did not have anorganized program such as this one. Buell G. Gallagher, the 7thpresident of CCNY, credited Condon’s zeal for the success of the program fordisabled students.

Her program, nowknown as the Accessibility Center, ensures students receive full participationand meaningful access to CCNY’s services, programs and activities. Collegesacross the world now have similar programs thanks to Condon. After the successof CCNY’s program, Condon went on to travel the world, reporting andresearching rehabilitation methods to make these programs better for students worldwide.

Moving out of theWWII era, the Civil Rights movement had a dramatic effect on the demographicsof the CCNY campus. During the “Five Demands Protest” at CCNY, Black and Latinostudents occupied the campus to call for change. The students demanded

- Aseparate school of Black and Puerto Rican studies

- A separateorientation program for Black and Puerto Rican students

- A voicefor SEEK students in the setting of all guidelines for the SEEK program,including the hiring and firing of all personnel

- That theracial composition of all entering classes reflect the Black and Puerto Ricanpopulation of New York City high schools

- That Blackand Puerto Rican history and the Spanish language be a requirement for alleducation majors.

One of the students at the forefront of these protests was Toni Cade Bambara, an activist, writer, and documentary filmmaker. Born Miltona Mirkin Cade in 1939, she was raised in NY, living in Harlem, Bed-Stuy, and Queens. After receiving her Master’s degree in American Studies in 1965, she was an English instructor in the pre-baccalaureate program, and the driving force behind the creation of the Center for Black and Hispanic Studies at CCNY. Her original proposal called for courses on American justice, African-American philosophy, trends in Western thought, and revolution, to name a few. During the protests, she also wrote for Observation Post, a now extinct CCNY newspaper. Her article “Realizing the Dream of a Black University” explained the demands of the students and argued for a more inclusive and representative campus.

Bambara also pennedan open letter to the Harlem ‘Blood Bothers’ near the end of the 60’s, urgingthem to come to CCNY and get an education. An excerpt from her letter reads:

“On the assumption that all of you mumblers, grumblers, malcontents, workers, designers, etc. are serious about what you’ve been saying (“A real education—blah,blah,blah”), the Afro-American-Hispanic Studies Center is/was set up. Until it is fully operating (fall ’69), the responsibility of getting that education rests with you in large part. Jumping up and down, foaming at the mouth, rattling coffee-cups and other weaponry don’t get it. If you are serious, set up a counter course in the Experimental College. If you are serious, contact each other. If you are serious, contact Don Alpert in the Finley Center (Experimental College).

Serious—

Miss Cade”

In the early 1970’sshe began her writing career, emerging as a prominent figure in Black women’sliterature. Her novels were mainly centered around Black men in America,covering racial tensions “in a tone more thoughtful than angry,” as C.D.B.Bryan wrote in a review of her book Gorilla,My Love. Other books by Bambara include TheSalt Eaters, Raymond’s Run, Those Bones Are Not My Child, Deep Sightings & Rescue Missions, andThe Sea Birds are Still Alive.

In the 70s, Bambaraalso traveled to Cuba and Vietnam to study women, and following her return tothe United States, she taught at Rutgers University, Duke University, and AtlantaUniversity, among others. Throughout her life, Bambara continued herinvolvement in Black liberation and women’s rights movements, writing novels,and producing social documentaries like The Bombing of Osage Avenue.

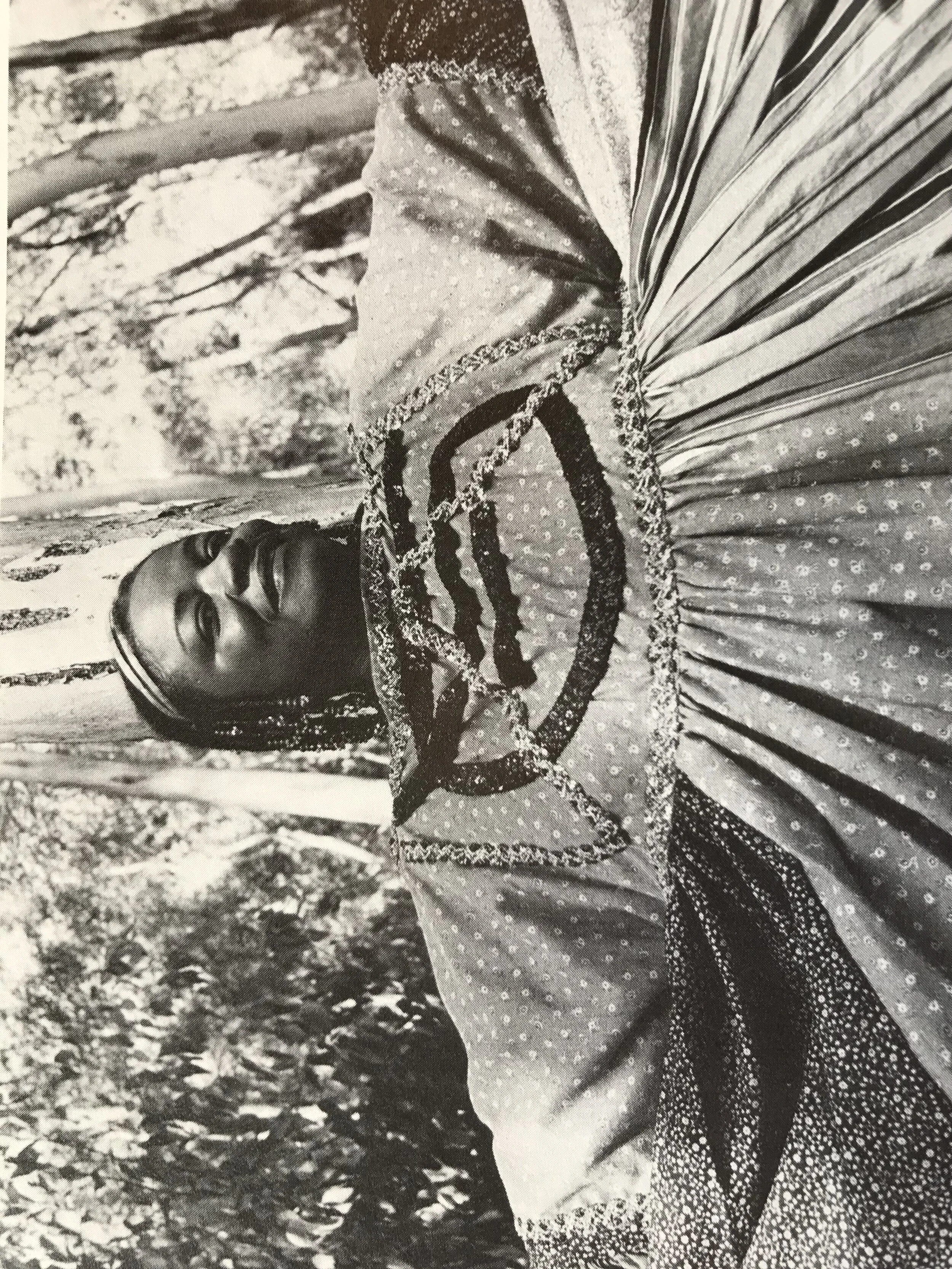

On the topic of the Civil Rights movement, one person cannot be forgotten. Faith Ringgold is an artist, writer, and most importantly, activist. Born Faith Willi Jones in Harlem circa 1930, she briefly enjoyed the fruits of the Harlem Renaissance, which was quickly overshadowed by the Great Depression.

Ringgold receivedher Bachelor’s degree in Fine Art from CCNY in 1955, and completed her Master’sdegree in Art in 1959, also from CCNY. Inher essay Bearing Witness, Ringgoldsays her artistic awakening was in conjunction with the Civil Rights movement.She witnessed violence and injustice all over New York but never saw itreported in the media. She used her art to bear witness to the changes takingplace in America, changes that were ignored by people in power.

In heressay Those Cookin’ up Ideas for FreedomTake Heed, Ringgold expresses her rage against the people in power in athree-page essay entirely in capital letters. She calls out the white men ingovernment, saying “THEY KNOW IT’S OKAY TO BE A CONSERVATIVE, A REACTIONARY, ARACIST, AND A SEXIST.” She continues to say, “IF THEY DON’T LIKE SOMETHING, ORIF THEY BELIEVE IT TO BE UNPATRIOTIC, IT IS OBSCENE.” Ringgold witnessedobscenities throughout her entire life: white supremacy, sexism, homelessness,poor housing, poor health care, broken school systems, drugs, and despair; andwatched the white men in power ignore it.

Throughout her lifeshe advocated for opening up space for Black artists in museums. She protestedthe Whitney Museum and the MoMA, calling for exhibitions focused on Blackartists that were often excluded from these prestigious museums. Her piece Hate is a Sin Flag, which depicted herexperience of being called the n-word while protesting the Whitney, is now apart of the Whitney’s collection. In 1971, she co-founded Where We At, a grouppropelling the work of Black women artists. In 1972, she worked with ArtWithout Walls to bring art to inmates and brought an installation to theWomen’s House of Detention on Riker’s Island.

Ringgold continuesto make art and speak on social issues around the world. She is widely knownfor her use of quilts to depict scenes of American history and politics. Shehas also published several books including 17 children’s books and her memoir We Flew Over the Bridge, The Memoirs ofFaith Ringgold.

These are just a few of the revolutionary women that changed CCNY, and the world. Their work broke barriers for women, people of color, disabled people and other marginalized groups. Today, there are hundreds of women at CCNY who continue to have a revolutionary impact on our campus, society, and world. Some of my biggest role models teach on our campus, like Linda Villarosa, Griselda Rodriguez, and Margarita-Asha Samad-Matias. This Women’s History Month, take some time to appreciate the work women have done to change our campus. The CCNY archives, on the 5th floor of the NAC Library has excellent resources to learn more about our history and the women who influenced it.